Science Storytellers: Connecting Kids, Scientists, and Science Writers at AAAS

Note: This post was originally published in The Open Notebook

For much of my career as a science writer, I’ve stood in the intersection of a Venn diagram connecting science journalism, science education, and science outreach (or engagement, as we’re calling it now).

It makes me a bit of a misfit, being neither full-time journalist nor teacher nor PIO. But I’ve long thought these communities have a lot to offer to—and learn from—one another. Here’s why.

I recently worked on a PBS KIDS science program called Plum Landing. One of the things I most loved about this program was its effort to get kids sharing their stories with us.

We invited them—through games, an interactive photo app, and a digital drawing tool—to go out into the world, record what they saw and what they did, and tell us what was awesome about it. The key point here being they told us, and not the other way around.

This got me thinking. Why don’t we, in the world of science writing, do more of this?

Truth be told, I’ve had a bee in my bonnet about this for years. People who study the science of science communication (yep, it’s a thing) have talked for some time about the deficit model—the idea that “the public” is an empty vessel waiting to be filled with the science information that we, the journalists and other providers of knowledge, fill. That we overcome perceived deficits in science literacy with more science.

But it turns out that’s really not effective in changing hearts and minds. That’s because the deficit model ignores the values, emotions, and motivations that shape people’s opinions and perceptions.

So when a colleague stood up during a AAAS symposium on science communication a few years ago and asked if we needed to change how we approach science communication, well, that bee in my bonnet became a noisy, buzzing hive.

A few months later, I heard a talk by the late David Lustick, a White House Champion of Change for Climate Education and Literacy and associate professor of science education at the University of Massachuestts at Lowell. He spoke of his work bringing messages about climate change to people as they went about their daily lives.

He did this brilliantly—with posters and placards on buses, subways, and other public spaces in Lowell and Boston. But he didn’t use those spaces to lecture. Through his ScienceToGo program, he used humor and artwork to invite people in.

Lustick spoke most passionately about Cool Science, a contest that asks kids to show what climate change means to them—through art. Winning entries are turned into posters displayed on the city buses and transit stations all over the city of Lowell, Massachusetts.

Like Plum Landing, Lustick’s program invited kids to be the messengers. He wanted to know what they had to say, wanted to give them a voice. I saw a lot of points of intersection in his work and the work that we did on Plum Landing, and used this for the basis of a symposium I organized for the AAAS annual meeting in 2016.

And that’s when the idea of Science Storytellers began to crystallize. AAAS is unusual in the world of scientific meetings in its open embrace of non-scientists. Its two-day event, Family Science Days—a huge indoor science festival—offers free admission to the public.

Breaking barriers, opening doors

AAAS is also the perfect place to start the hard work of breaking down barriers and getting kids talking to scientists one-on-one. So last summer, I pitched an idea to the team at Family Science Days: to create a program where we ask kids to become storytellers for the day, giving them a place to tell us what science means to them.

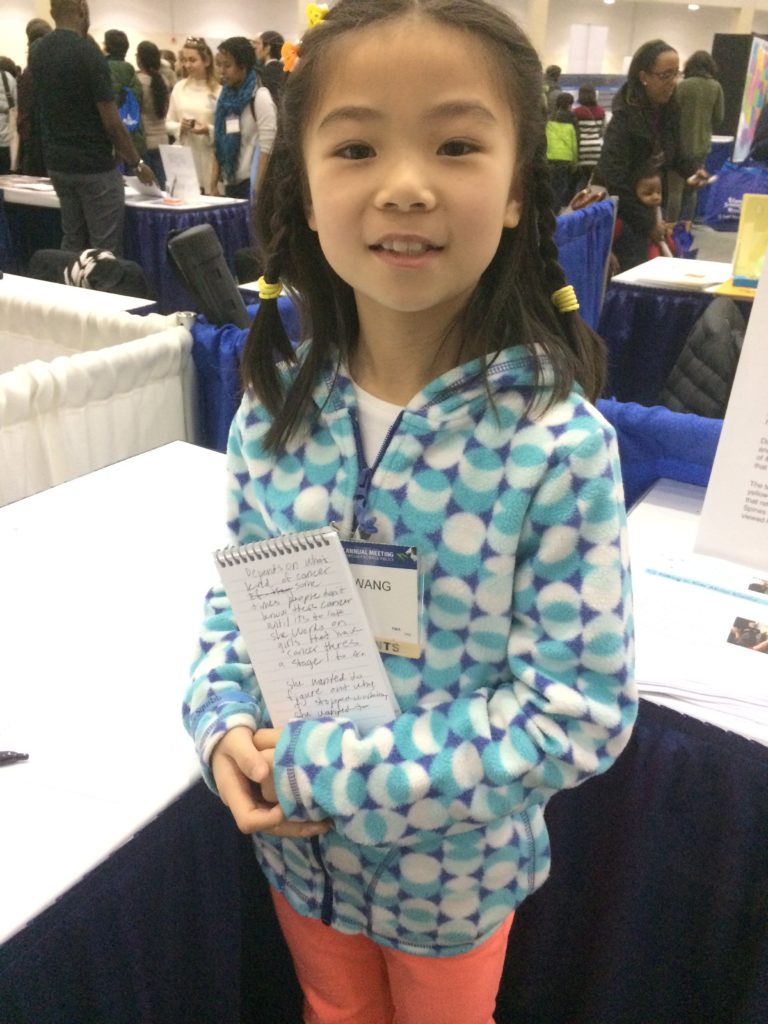

We would identify scientists at the meeting who would like to connect with kids and invite them to our booth, or send families to meet them at the poster session. We would show the kids how to talk with the scientists in the manner of science journalists: What’s your work all about? How did you get interested in that? Why does it matter? What’s your favorite flavor of ice cream? And then, we’d ask them to share their stories with us.

AAAS green-lighted the proposal. And The Open Notebook‘s Siri Carpenter agreed to partner with me (that’s a fancy way of saying “donated her time and expertise with the promise of nothing more than a swag notebook and a brandy old fashioned as compensation”) to create this program.

The Burroughs Wellcome Fund, which supports TON’s early-career fellowship program,generously offered to fund the design and production of materials we’ll be handing out at AAAS. TON’s and BWF’s support was key—without it, I could not have gotten this project off the ground.

But with their support, we’ll be spending two days at AAAS acting as matchmakers—introducing kids to real-world scientists, stepping back, and letting the conversations and stories flow.